The Ultimate Guide: Writing Introduction

This post contains affiliate link.

I had a love and hate relationship with my thesis. One of the sections that I hated was the introduction.

I felt that the introduction is one of the most challenging sections in thesis or manuscript to be prepared.

When I was a student, I dreaded getting my introduction finished. Even after I had my PhD, writing an introduction for a manuscript was like walking in the jungle.

It took me a while to figure out what is the secret formula until I finally found it and I completely fall in love with writing the introduction.

Well, not really. Still hate it sometimes. Told you it is a love-hate relationship.

So, what is the secret formula?

STORY.

According to Joshua Schimel, the author of Writing Science, scientists should be able to effectively communicate their work by becoming good storytellers.

You might say, "What?! Do you expect me to write stories like Star Wars or Harry Potter? I'm not writing science fiction! I'm doing serious work here! I put my blood and sweat to do my Master/PhD and you ask me to write a story?

Seriously???"

Yup!

Seriously.

Write a story.

Because the effort that you take to get your results, and painstakingly write your thesis is worthless if you can't convey the message of your research. You see, people understand better from a story because they can relate better.

So, how do we write a story in academic writing?

STRUCTURE.

With the right structure, you can carve our research into a compelling story that guides people to understand your hard-earned effort better.

A bit of warning though...

Writing an introduction with a story and structure is easier than not knowing what to write, but still requires some creativity and skill.

So, it needs practice. Most importantly, get feedback. Then, get your colleague to read it. See if they can understand your story.

You can do it. I know.

I'm here to hold your hands to write a good introduction by giving a step-by-step guide with some examples here and there.

Here’s the breakdown of what we'll cover:

What is introduction in research?

What is the purpose of introduction in research?

What is the importance of a good introduction?

What tense should be used in introduction?

What's the difference between introduction and literature review?

When should you write the thesis introduction?

Steps in writing the thesis introduction

What are the common mistakes in introduction?

How long should a thesis introduction be?

Let's dig in.

WHAT IS THE INTRODUCTION SECTION?

Introduction not only gives the background of your study but also establishes the context of the problem and research gap that you're trying to resolve. It also provides a road map, which is your objectives, to what you’re going to do to resolve the problem.

WHAT IS THE PURPOSE OF INTRODUCTION IN RESEARCH?

Imagine watching a movie without any introduction to the characters and situation.

The movie straights away jump into a scene where a troubled person is in distress, then suddenly he becomes a hero that saves the world.

You’ll probably be wondering….”What on earth? Who is that guy? What problem is he facing? What problem is the world facing?”

The same questions might pop into your head if you read a thesis that jumps straight into other sections of a thesis.

Assuming that your thesis is a movie, the introduction briefly provides the who, where, when, what, why and how of your research.

Without an introduction, your readers would be lost.

WHAT IS THE IMPORTANCE OF A GOOD INTRODUCTION?

The aims of the thesis introduction are:

to provide sufficient background by giving the context of the problem and the importance of solving the problem,

to provide previous related research that shows any inconsistent, insufficient, biased or incorrect information to establish the research gap,

to convey the importance of your research, whether it's empirical, theoretical, methodological or policy-relevant,

to lay out the roadmap of your research by providing the research question, hypotheses and objectives.

With these things in place, you are motivating and preparing your readers to further explore the next sections of your thesis (literature review, materials and methods, results, discussion and conclusion).

What tense should be used in introduction?

It’s a cocktail of tenses depending on the situation:

Present tense- use it when you’re expressing information that is well known to be true. For example, “The earth is round.”

Past tense- use it when you’re describing previous research. For example, “Kit et al. (2020) discovered the latest species of scald fish”

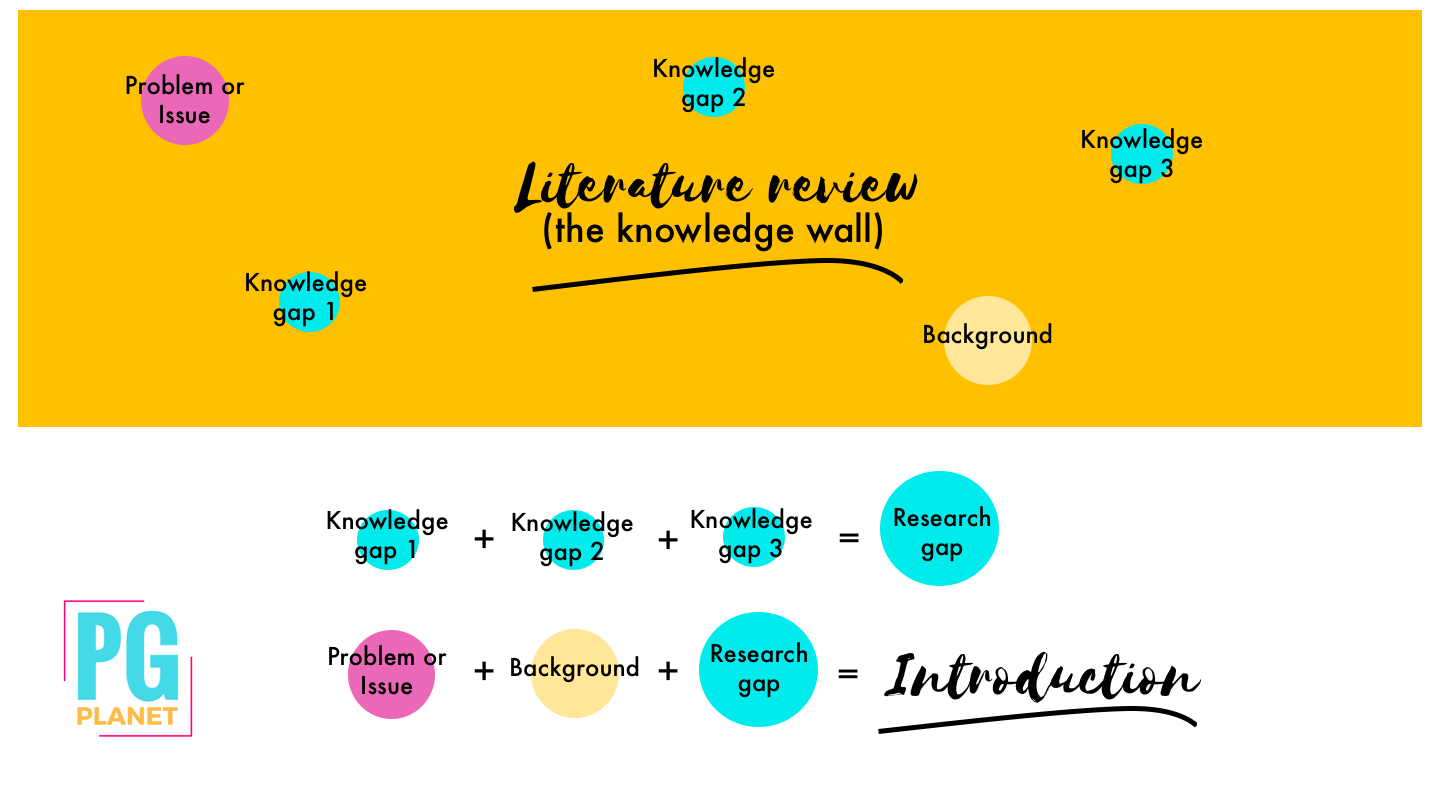

What's the difference between introduction and literature review?

Basically, both are inter-related. Literature review has information that can be used for both introduction and discussion.

A literature review is a wall of knowledge where all the necessary information about your study should be included. It is the core knowledge of your research.

An introduction is the holes on the wall (the literature review) that needs to be filled up by your research.

The challenge is to frame the introduction into a knowledge gap by synthesising the knowledge in the literature review into a convincing story.

The difference between a literature review and an introduction.

When should you write the introduction?

I would recommend writing a thesis introduction after you have completed your literature review.

Why?

Because by that time, you have read plenty of past studies that enables you to know the subject from a broad perspective to the information that narrows down to the niche you're studying.

At this point, you're almost the Yoda of your research (you become the Master Yoda once you defend the thesis).

Since the introduction should be brief and straight to the point, the knowledge establishment enables you to filter and provide only the crucial background, along with the research gap, problem statement and objective.

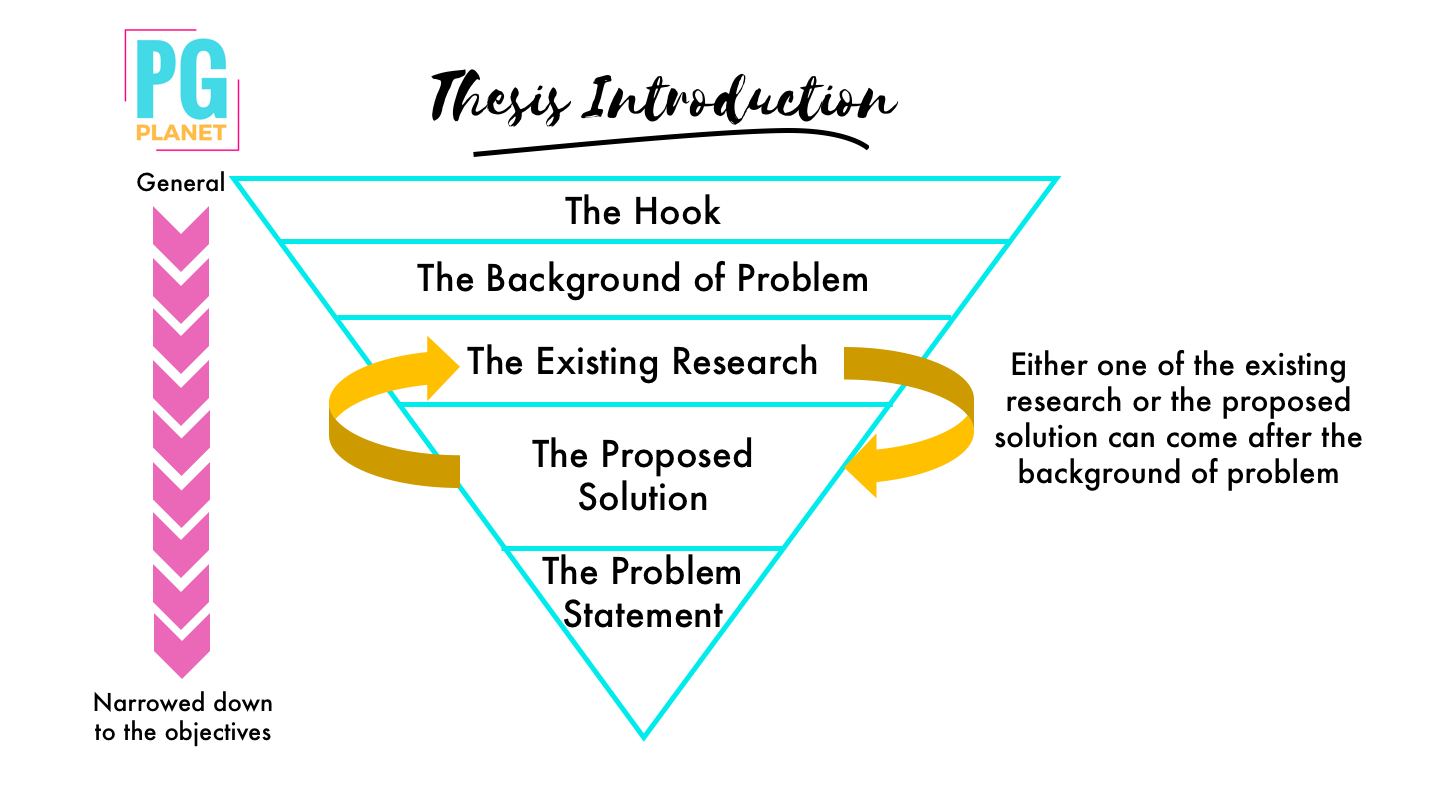

Steps in writing the thesis introduction

Steps in writing the thesis introduction

So what should be in the thesis introduction? I've outlined 5 elements that should be in your introduction. This structure gives your story a compelling opening to your thesis.

1) THE HOOK

A movie introduction with a slow or boring beginning will not attract watchers; neither does readers in our case of academic writing.

So, how do you start a research introduction?

One of the most crucial parts of an introduction is the first sentence.

It should start with a killer hook that will grab the attention or spark the curiosity of your readers. You should always consider the type of audience that is going to read your writing.

For a thesis, the readers are more likely to be academicians, researchers or graduate students that are looking for information in your field. Always start with a general statement.

There are a few ways you can come up with a good hook:

The problem/issue - Start with the bigger context of the problem that you plan to solve.

Example: Procrastination in academic writing has been a problem for many graduate students that leads to graduation delay.

Statistics or numbers - Numbers can surprise your readers. Statistics and numbers are a good attention grabber. The numbers don't have to be from the previous research, but you can pull the numbers from reliable statistics resources, for example, Department of Statistics in your country.

Example: Malaysians consume 98.4% white rice as opposed to India (~75%), Japan (58.9%) and China (30%).

Interesting facts - This hook can be a little bit tricky. It should be something that is not well-known that triggers the surprise button.

Example: Recently, X et al. (2019) discovered male spiders with a paddle on the front left leg which functions to ensure the female spiders are totally attracted to the paddle dance. The dazzling dance eventually gets the male spiders to mate instead of being killed by the female spider.

The benefits - Generally, point out the benefits of your subject in your research. This kind of hook will generally imply, "You should read this because it's important."

Example: Fruit consumption was proven to reduce the risk of cancer and cardiovascular diseases.

Misconceptions/Theory/Framework that you want to challenge- Strike a statement that causes your readers to be conflicted with their previous belief or values.

Example: Many scholars believe that theory A is closely related to the formation of fibre strings in the core of fish muscles, but theory A is missing the mechanism in the initial stage of protein X.

Definition - Let's face it. Definitions are boring if it's commonly known. But definitions can be a hook if it's unknown to the readers, especially if you add interesting facts to the definition.

Example: As the name implies, resistant starch is starch that resists digestion in the stomach and small intestine of a healthy human (Englyst et al., 1992), ultimately categorizing resistant starch as fibre.

So, find your hook! You can choose whichever best suits your study. Your hook may comprise of more than one of the hook types. As long as the hook phrase leads to the introduction of the problem or issue you're attempting to solve, you're good.

2) THE BACKGROUND OF PROBLEM/ISSUES

The first sentence of this section should be your hook. Then, you can expand it further by introducing the problem or issue you're trying to solve. Just like you're introducing the main leads in a movie, start with highlighting the subject that needs the problem-solving. Then, lay out the vital context, parameters, variables or other essential elements in your research. Use the questions below to help you carve the background story.

What is the problem (organize from larger to smaller perspective)?

What is the context?

What is the background?

What are the terms and/or definition related to the problem?

Why is the problem important to be solved? What is the motivation to solve the problem?

What is the predicted effect of not solving the problem? Who/what will be affected?

Who are the characters (parameters, variables, samples, method)? How are they related? Why are they important? Why choose them?

3) THE EXISTING RESEARCH

The next step is to state the existing related research that attempted to solve the same/similar problem. This part is where your literature search of the past studies comes in handy. You don't have to list down every past studies available, but choose the ones that are crucial to establish your research gap. It should be written in a way that will show how your study will fill up the gap in the next section.

What is the existing research/solution/theory/method that has been done to solve the problem?

Which research is the best, but still needs improvement?

What is/are the limitation/s in the existing solutions?

What are the contradicting results in previous research (conflicting outcomes)?

What is the bias/inconsistent/insufficient information in past studies?

Which area/factor/variable can be improved to solve the problem?

The above questions will lead to the establishment of the research gap.

4) THE PROPOSED SOLUTION

Once you have identified the research gap and the need to find a better or improvised solution than past studies, it's time to introduce your solution, i.e., your research. Answer the questions below to come up with the story of your solution.

What is your solution that fills up the research gap?

Why is it important?

What is the background/definition of any parameters involved with your solution?

What are the boundaries of your research?

What is/are the advantage/s of your solution?

What is/are the related research that shows the effectiveness of your solution (if any)?

5) THE PROBLEM STATEMENT

In this section, you have to briefly but concisely summarize the second, third and fourth sections above into a problem statement that leads to research questions and hypotheses. Finally, lay out the road map of your study by giving the objectives. To guide you, answer the questions below:

What's the context of your problem?

What is the knowledge gap you are trying to fill?

What are the research questions you're trying to answer?

What is the hypothesis of your study (if any)?

What are the objectives that will help you answer the research questions?

All the steps should be in order except for step 3 and 4. You can write the existing solutions and proposed solution interchangeably, depending on how you carve the story. If your solution is novel and has never been done, you can always go with the existing solutions first.

But if your solution has been applied in a different context, you might want to start with the proposed solution first, then write on the existing solution within a different context to come up with a narrowed down research gap that leads to your solution in another context.

What are the common mistakes in introduction?

Common mistakes in introduction

Too general

How general should it be? It should be broad enough to introduce the context within your study scope.

For example, if you're studying how a specific complex carbohydrate in a plant help to manage a particular disease, don't start with the definition of carbohydrate. Instead, you may start by revealing the shocking statistics of people affected by the disease and why it's crucial to manage the disease.

Then, narrow it down to the different types of complex carbohydrates that were previously studied. If there's a lot of study on the same complex carbohydrate you're studying, you may dive into that straight away. Establish the research gap (the area that needs to be studied) and then focus on the importance of your research.

Bad flow

Whenever you watch a good movie, the plots changed seamlessly. You don't watch a movie that shows you a lovebird randomly meet, and then the next plot shows they have 17 grandchildren! What happened in between those plots?

The same thing goes with your introduction. Your sentence and paragraphs should flow seamlessly to maintain the train of thoughts of readers. If the train of thought is constantly disrupted, your readers are going to be all confused and eventually lose interest.

The problem statement is not clear

The favourite phrase for problem statement is always, "No study has been done on this topic."

I'm not saying this phrase is wrong. But whenever I read this, I wonder if the authors have really gone through extensive search. Have they searched and read ALL the related papers and finally concluding, there's no study conducted? If it is true, then fine.

But most of the time, I doubt it.

The best way of framing your problem statement is by clearly identifying the research gap that needs to be addressed. Refine the research gap by exposing the weakness and/or giving conflicting statements of past research.

For example,

"Among the research conducted to solve problem _____, research by X, Y and Z were extensive but focused mainly on factors A, B and C. However, the researchers failed to address factor D, which was found to play a critical role in ________. Although researchers O and P studied the D factor, the results were inconsistent and contradicted the A mechanism <THE RESEARCH GAP>. D factor is important to be explored in determining the root cause of _______<IMPORTANCE OF FILLING THE RESEARCH GAP>. Hence, research using method/theory X is proposed to further explore the possibilities of factor D <INTRODUCE YOUR SOLUTION & ELABORATE FURTHER>."

Offering solutions before defining the problem

I'm not sure how the rotary dial telephone got famous in the first place. But imagine if it was introduced by telling people all the remarkable features of the phone, like it has a rotary dial and uses electric signals that travel through cables. Would you be interested in buying it if you've never heard of what a telephone is?

If I'm a salesperson that wants people to be interested in buying the never-heard technology, I would start by addressing the problems people were facing at that specific time. That is, they have to travel far to tell a message that cost them time and money. Then, I would say to them WHY they must have the telephone and how it would change their life.

The same scenario is applicable to your introduction. Some published papers often start their introduction with the solutions they're offering. If you do this, it's like asking someone to try your new invention, without knowing what and why it's for. If I read these kinds of papers, I will ask questions like, "What is this tool for? Why invent this new method? Who is the solution trying to help?" Then, I'll get tired of trying to find the answers to my questions because all the answers are stated later in the introduction or never mentioned at all.

So, always start your introduction with the background and context of your problem. Offering the solution first is a big no.

How long should a thesis introduction be?

An introduction should be precise and concise.

The introduction length should be long enough to introduce the characters, define the problems, give existing solutions and the limitations (your research gap), provide your solution, give a problem statement and list your objectives.

I would recommend around 700-1500 words or 5-10% of your overall thesis. This length is the norm in my field.

Alternatively, look at the introduction of the existing thesis in your related field to have a good idea of how long it should be. Also, identify the structure and the story flow. There could be some differences from the ones suggested in this post.

Conclusion

Even if you are clueless….

…..or stuck….

….or have no idea what on earth you’re doing….

Just know that you are capable of writing your thesis introduction without getting stressed out or having the "writer's block syndrome".

You now know what should be in your introduction.

In a nutshell, your introduction should have five elements:

The hook

The background of problem/issues

The existing research

The proposed solution

The problem statement

Always remember that your work is important, but if you don't write it well, people may have the perception that it's worthless.

So, introduce your study clearly and concisely.

Let the readers know that your research matters.

Reference

What's your process of writing the introduction? Do you have any other tips that I never mention in this post?